A ghost of Angola's past, Luanda's bullring awaits new life

Source: AFP

PAY ATTENTION: Click “See First” under the “Following” tab to see Legit.ng News on your Facebook News Feed!

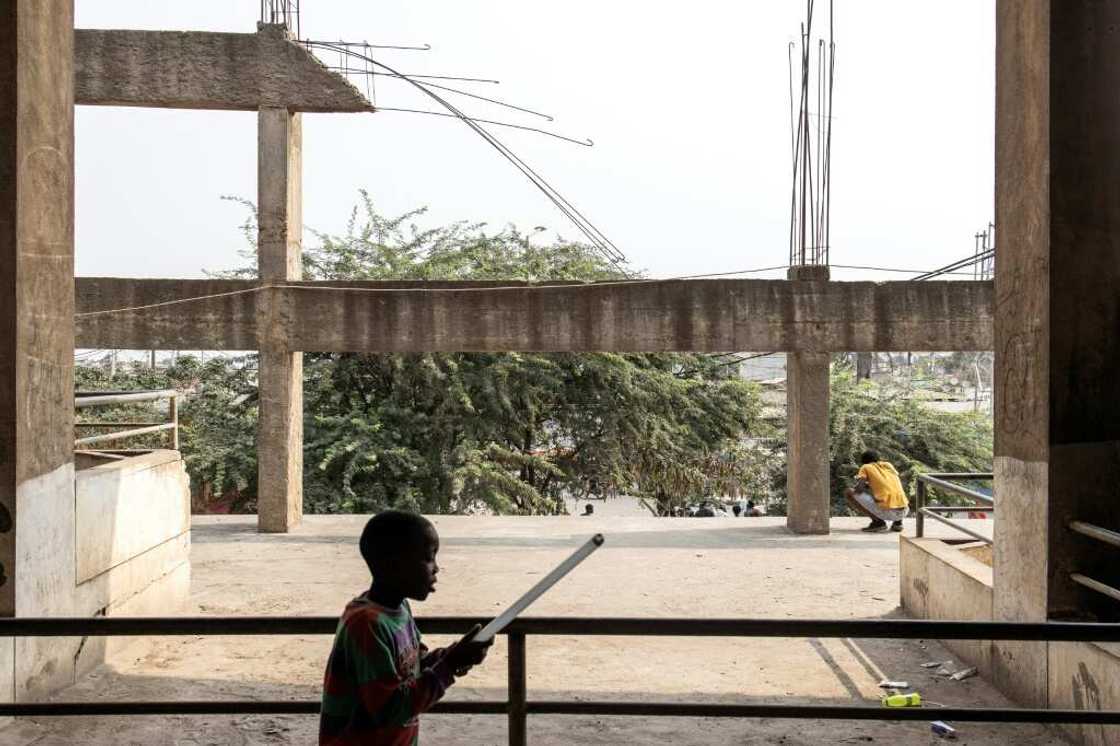

Around the corner from a congested Luanda street, partially covered by a thick row of little shops and food stalls, stands a dilapidated concrete bullring -- the vestige of Angola's colonial past.

Once a thrust of city life, the arena has been abandoned for decades, and repeated government promises to renovate the venue have yet to bear fruit.

The neglected ring is entered through an almost-hidden, corrugated iron gate, and steps are lined with rubbish. The air is permeated by a thick smell of urine.

Numbers for the stands can still be seen on the worn-out walls, half-covered by graffiti.

Up to the mid-1970s, Luanda residents crowded the stadium's 20,000 seats to watch bullfights or "touradas" -- a violent pastime pitting man against animal that was introduced to the southern African country by its Portuguese colonisers.

Unlike Spanish bullfighting, under Portuguese rules the bull is not killed in front of the audience in the arena but usually slaughtered afterwards.

PAY ATTENTION: Follow us on Instagram - get the most important news directly in your favourite app!

Locals would form long queues to watch a bullfighter named Chibanga from Mozambique, who was a marked exception in a sport dominated by whites.

Source: AFP

When Chibanga fought, "it was a big event, everyone wanted to see it," recalls Antonio de Oliveira, also known as "Delon".

He heads Angola's Carnival Association, a cultural group that now occupies the premises.

"He was a great model because it was believed that only the white Portuguese could practice the tourada, not the Africans", added Delon.

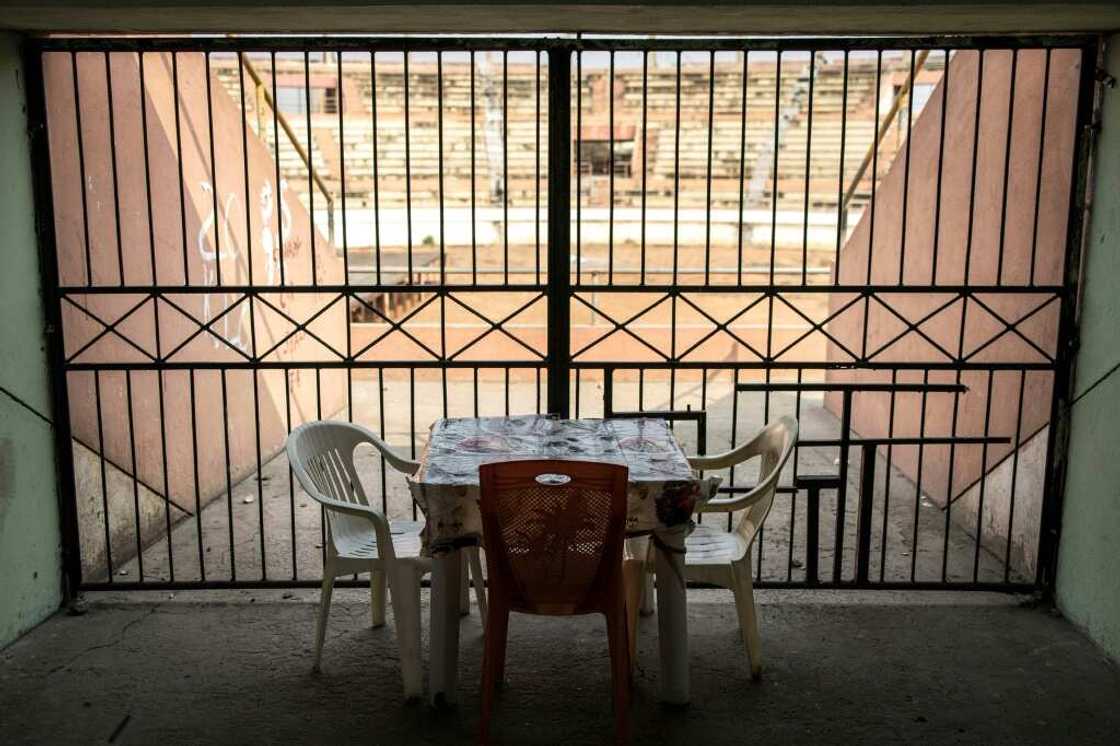

The arena's sand circle and seat rows are still intact but have long fell silent.

After independence in 1975, the MPLA, a former Marxist liberation movement, came to power and banned bullfights, which they saw as a reminiscence of the violence of colonial rule.

"They thought ... it necessary to breathe new life into" the country, says Delon.

Warm beers, no change

Having been first introduced only about 25 years earlier, the touradas disappeared without trace.

The arena became a concert venue, hosting some of the biggest names in central African music, from Pepe Kalle to Koffi Olomide.

But as a lengthy and brutal civil war consumed the country, it slowly fell into decay and started to draw refugees looking for shelter rather than entertainment.

Source: AFP

Some squatted inside, while others built homes around it.

"We saw this abandoned space. It was in terrible conditions ... but we had no other option," says Francisco, a former soldier, who came to live in the area with his family in 1998.

The civil war ended in 2002, but here -- as in the halls of power, where the MPLA have remained since independence, having won the most recent narrow and disputed election only last month -- little has changed.

The provincial governor last showed up for an "assessment" tour in 2019, locals say.

"There is some funding from private sponsorships but little else," laments Delon, who would like to see the place spring back to life.

"We have a great cultural heritage, dance, music, cinema, crafts," he says.

Meanwhile old-timers on plastic chairs drink lukewarm beer as they reminisce about the good old days under the stadium's huge concrete beams.

Source: AFP

A few squatters still live on the upper floors, where iron bars and chained dogs seal the entrance to dwellings veiled behind large red and black national flags.

Francisco, the former soldiers, and others like him who live in cinder block houses that sprawl around the building would see their homes razed to make room for a huge parking lot if the current renovation plans were to get underway.

"After twenty years here, the government is telling us to move out. We don't have a problem with that," he says looking at the old bullring.

"One day it will be renovated" he repeats. "We are waiting".

Source: AFP