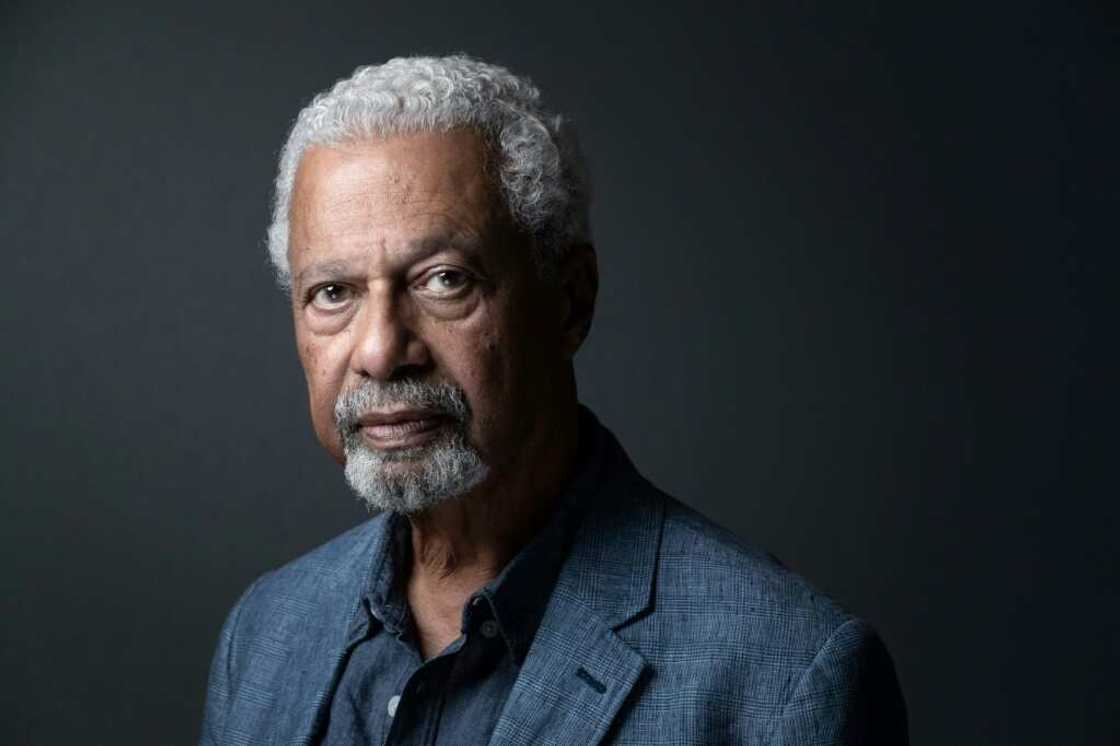

Nobel winner Abdulrazak Gurnah: 'It's good to make right-wingers cry'

Source: AFP

Abdulrazak Gurnah, the British-Tanzanian Nobel-winning writer, has spent a lifetime confronting colonialism and racial politics -- and welcomes a new generation keeping these issues alive.

The author has suddenly become a famous name in his 70s after winning last year's Nobel Prize for Literature.

Drawing on the brutal realities of colonialism in Africa and the dislocation and poverty he experienced when he came to England, novels such as "Paradise", "Desertion" and "Gravel Heart" explore racism, exile and the legacy of European domination.

Gurnah says his generation had a particularly complex relationship with colonialism.

"For people of my father's generation, colonialism was something they saw arriving, implanting itself, dominating. But they didn't lose a sense of who they were," he told AFP during a trip to Paris.

"(My generation) couldn't just brush it off. We could see that in fact much has been done -- progress in medicine, technology, engineering... we are more urgently forced to try and engage and understand that relationship."

PAY ATTENTION: Join Legit.ng Telegram channel! Never miss important updates!

He welcomes the recent wave of anti-colonial protests, often focused on statues and other symbols of the era.

"I don't care if they topple statues or not. But the symbolism is good," he said.

"And it provokes all these right-wingers to come out and start crying and complaining. Good. It means the issue is kept alive."

'A difficult time'

Gurnah grew up in Zanzibar, which became part of Tanzania after gaining independence from Britain in 1963.

A year later, a Communist-inspired revolution led to problems for Gurnah's Arab-origin family.

His father came from a Yemeni family and his uncle was a wealthy trader of fish, dates and spices.

They became targets when the Communists overthrew Zanzibar's sultan and his mainly Arab government.

"It was a difficult time for everybody, particularly people who the government considered to be foreigners. It was part of a racialisation process, quite unjust," Gurnah recalled.

His family supported the Zanzibar Nationalist Party, which had tried to create a shared identity rather than focus on separate ethnicities.

Source: AFP

"We were saying: we're Zanzibaris -- we're not Indians, Arabs, Africans. We don't want to be racialised," he said.

"Of course the racial politics won, but I still want to adhere to: I'm a Zanzibari, I'm not a Yemeni, this or that, or an African."

That debate found strange echoes after his Nobel victory, with Arabs seeking to claim him as one of their own.

"The Arabs celebrated me as a Yemeni writer. I said well, fine, if you want. That's not how I feel, but... it makes everybody happy, so why not?"

'African literature'

Gurnah fled to Britain and spent years in poverty before managing to educate himself into a career as an academic and author.

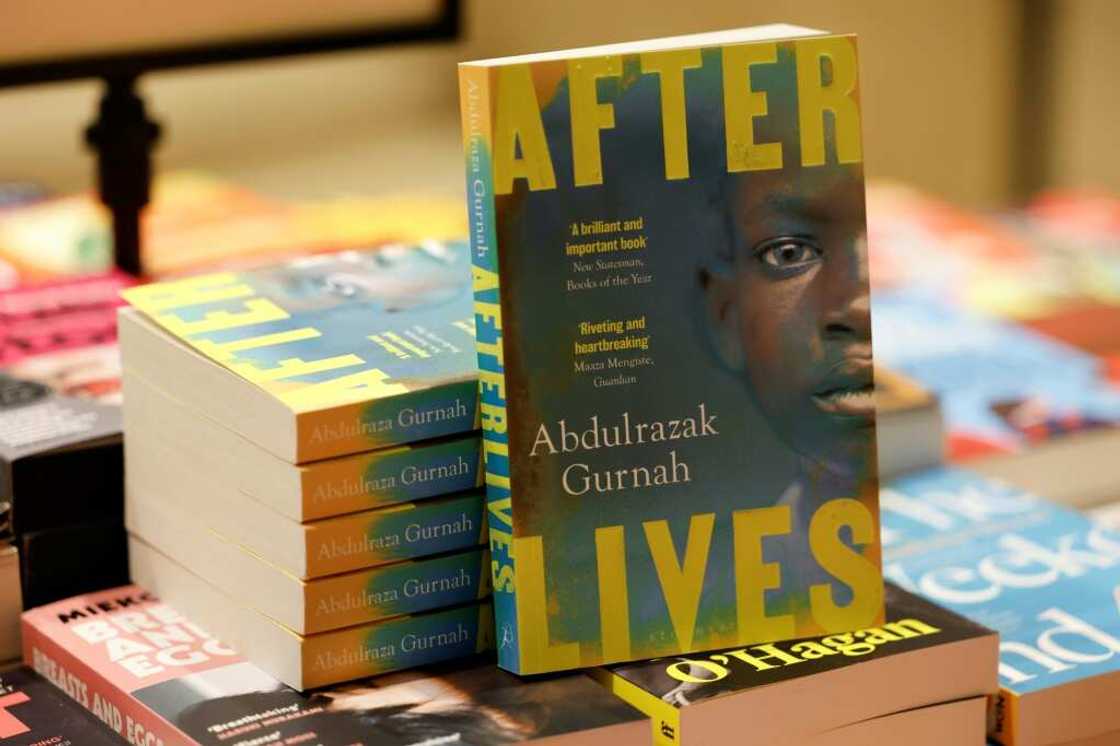

With South Africa's Damon Galgut winning the Booker Prize and Senegal's Mohamed Mbougar Sarr becoming the first sub-Saharan African to win France's Prix Goncourt, 2021 proved to be a landmark year for African literature.

Source: AFP

Gurnah knows the label of "African literature" is far too vague since it encompasses such a vast and diverse continent, but he takes a relaxed attitude.

"Those who use the term often already have a conception of African literature," he said. "They might exclude white South Africans, or North Africans, or Ethiopians and Somalis."

"(But) if we use it symbolically, it's OK, I can live with that... and I don't want to argue with anybody."

Source: AFP