Eyeing victory, Italian right rallies ahead of vote

Source: AFP

Italy's right-wing parties will stage a joint rally Thursday in a final push ahead of elections forecast to install a one-time fan of Mussolini as the country's first female prime minister.

Giorgia Meloni's eurosceptic, ultra-conservative Brothers of Italy was leading the last polls published two weeks before election day Sunday.

She and her allies, Matteo Salvini's anti-immigration League and ex-premier Silvio Berlusconi's Forza Italia, look almost certain to form the first far-right led government in Rome since World War II.

The elections in Italy, the eurozone's third largest economy but plagued by weak growth, colossal debt and unstable politics, are being closely watched in Brussels.

Meloni has sought to reassure investors worried about her links with Italy's post-fascist movement, while at the same time wooing voters disaffected with the status quo.

"As Gandhi said, 'first they ignore you, then they mock you, then they fight you. Then you win," she tweeted Wednesday, with a photo of her fingers formed as a V for Victory.

PAY ATTENTION: Follow us on Instagram - get the most important news directly in your favourite app!

Concrete measures

Meloni, Salvini and Berlusconi -- who at nearly 86 has conducted a largely virtual campaign so far -- will hold a rally in Rome Thursday evening before a final day campaigning ahead of a news blackout.

Source: AFP

Runaway inflation, a looming winter energy crisis and tensions with Russia over the war in Ukraine have dominated debate in a country only just recovering from the trauma of coronavirus.

Europe has also loomed large, with Italy set to receive almost 200 billion euros of EU post-pandemic funds by 2026 in return for structural reforms long demanded by Brussels.

Meloni no longer urges an exit from the euro but has made clear she will assert Italy's national interests, while the right-wing coalition's programme calls for a review of EU rules on public spending.

The coalition members do not always see eye to eye, however, raising concerns about the stability of their potential future government.

Source: AFP

Meloni and Salvini both pursue a nationalist "Italians First" agenda and demand an end to mass migration, while emphasising traditional family values and Italy's "Judeo-Christian" past.

But while Salvini has long admired Russian President Vladimir Putin and has criticised Western sanctions over Ukraine, Meloni is strongly supportive of Kyiv and their coalition is committed to NATO.

Their tensions have added some drama to a campaign otherwise subdued by the almost inevitability of the right's victory since July, when Prime Minister Mario Draghi called the snap vote after his coalition collapsed.

Flavio Chiapponi of the University of Bologna said it was "one of the worst election campaigns of the post-war period, there was no confrontation on policies or concrete measures to be taken".

Undecided

In the last general elections in 2018, Brothers of Italy -- born a decade ago out of the post-fascist movement founded by supporters of dictator Benito Mussolini -- won just over four percent of the vote.

Its meteoric rise has been attributed to Meloni's straight-talking style and her party's outsider status, as the only one untainted by the compromises required of being in government.

Source: AFP

The 45-year-old was Italy's only opposition leader for 18 months after all the other parties joined Draghi's national unity coalition in February 2021.

Brothers of Italy was last polling at around 24-25 percent, ahead of the centre-left Democratic Party on 21 or 22 percent, followed by the populist Five Star Movement on 13-15 percent.

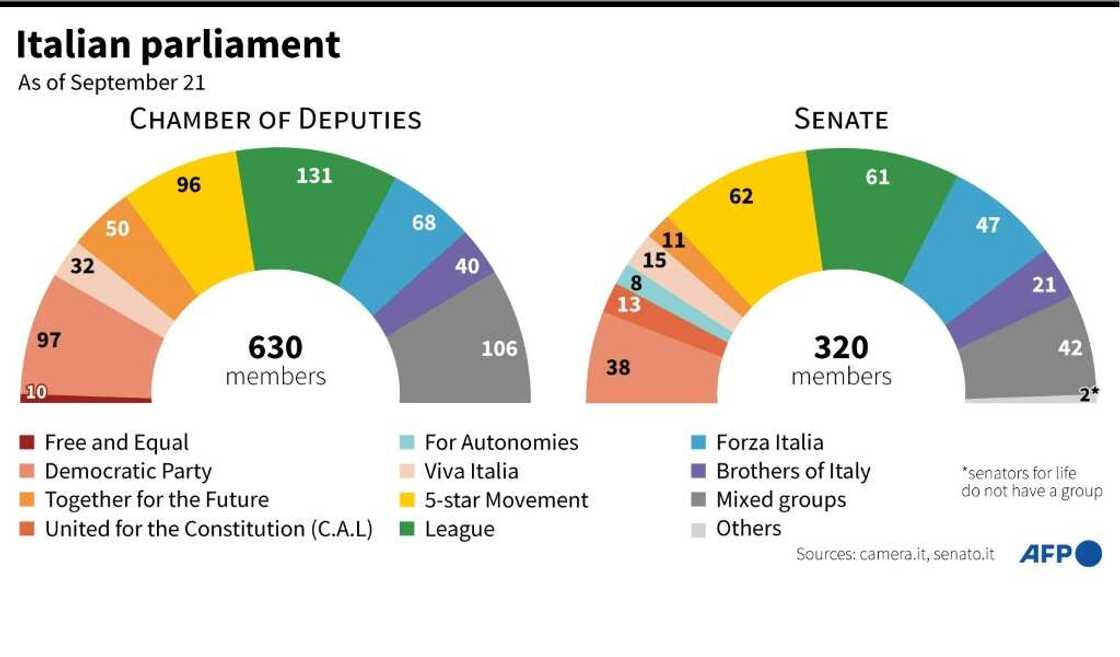

With her allies -- the League around 12 percent and Berlusconi's party at eight percent -- Meloni's coalition looks on course to secure between 45 and 55 percent of seats in parliament.

But Democratic Party leader Enrico Letta is putting his hopes in the 40 percent of Italians who say they either will not vote, or have yet to decide.

And experts caution that in a country that has seen almost 70 governments since World War II, predicting politics is notoriously difficult.

"In Italy, the election is decided the day people go to vote," noted Marc Lazar, professor at the universities of Sciences Po in Paris and Luiss in Rome.

Source: AFP